If you’ve ever watched Big Hero 6 or Real Steel and felt that tug - the feeling that robotic games should exist outside the cinema - you already understand why Robomates began. We didn’t start with a business plan or a six-figure prototype fund; we started with a stubborn question: could we turn the cinematic fantasy of dynamic, characterful robots into something you could actually play with in your living room? Not a research demo, not a fragile showpiece, but a game - fast, strategic, chaotic in the right ways, and deeply physical. One vision, a pile of ideas, and an even larger pile of constraints. That’s the story.

The first attempt followed the dream literally: small humanoid battle robots. It looked the part. Arms, legs, the promise of grapples and throws. We even got them working enough to give us a glimpse of what could be, but it came with the cold reality that kills many good ideas - cost and fragility. For a consumer product, humanoid robots are an engineering tax you keep paying: too many joints, too many points of failure, too many repairs between moments of joy. You can toughen them, but they get bigger, heavier and more expensive. You can cheapen them, but the experience falls apart. We realised we were solving the wrong problem.

The right problem wasn’t “How do we make humanoids cheap?” but “How do we keep the drama while changing what the robot looks like?” So we switched to wheeled balancing robots. They move with personality. They lean, dart, feint, and above all - they can fall. That “fall” matters far more than it sounds. In the context of a game, it’s a universal, instant cue for defeat. No having to look at the scoreboard, no extra logic to explain. The robot goes down: it’s out. That single physical gesture did more for game feel than any extra servo could.

We built a quick-and-dirty trial and invited friends to play. It wasn’t polished. It wasn’t wrapped in glossy plastic. But every component was properly modelled and the device was engineered to last long enough to get the data we needed; we weren’t cutting corners, just choosing the shortest path to truth. The truth came quickly: people were invested. They took sides, they shouted, they plotted little tricks and traps, they named the bots. That was our green light. The fun was there. The market will forgive a rough edge; it won’t forgive boredom.

Robomates first proper test game

With that signal, we pushed to a second version: sleeker engineering, tighter tolerances, a more deliberate shape. It ticked all the “proper product” boxes, and yet something felt off. The footprint was wrong. Set up two or three robots and their play area, and the whole game took over a room. That’s wonderful for a lab or a trade show, terrible for the realities of home life. You don’t want to rearrange furniture to play a ten-minute match. The constraint sharpened: this had to be a tabletop experience. Same adrenaline, same drama, but condensed to the size of a board game. If we could do that without neutering the physics, we’d have something that could live in any household and make sense from the first minute.

Miniaturisation sounds glamorous until you’re the one trying to cram physics, power, radios, sensors, and structure into a volume not much bigger than your palm. The hardest part isn’t drawing a pretty shell; it’s packaging. Too many engineering teams start outside-in: they sketch the silhouette, sign off an aesthetic, and then spend months trying to wedge reality into a shape that doesn’t want to accept it. That path burns budgets and patience. We made a different choice - what we call the shrinkwrap method, borrowed from how Formula 1 cars are designed. In F1, you start with what physics demands, the engine, cooling, fuel, suspension, wiring and then “shrinkwrap” the body and aerodynamics around it, taking only the absolute minimum internal volume you need.

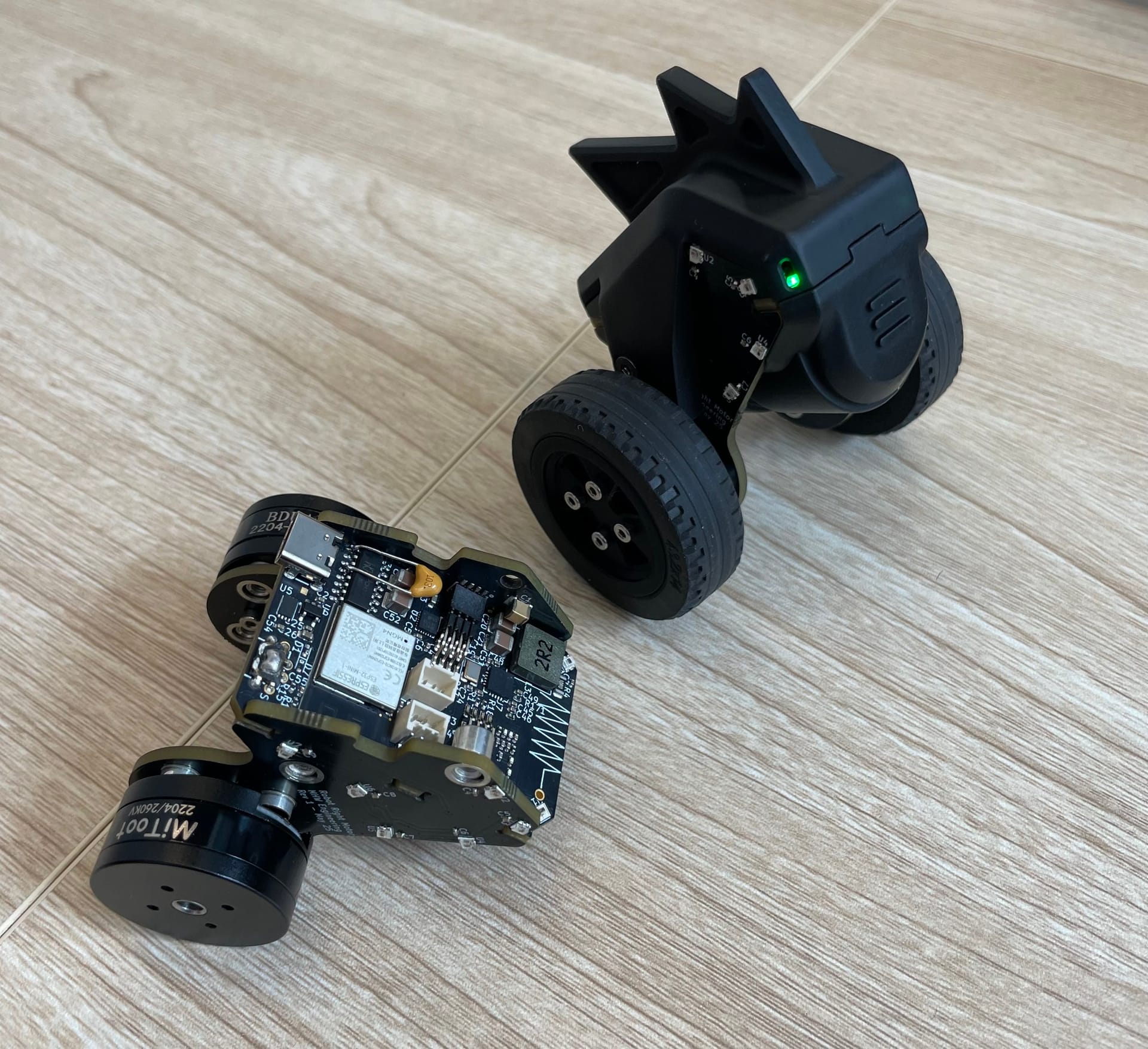

First, we defined a Robmate from physics, placing all the heaviest components in such a way that its centre of gravity was in the right place asking qns such as. What is the ideal wheelbase for agility without toppling? What does “responsive” actually mean in terms of moment of inertia? These are not philosophical questions; they are 3D physics constraints. Then we laid out every essential component: microcontroller, IMU, battery, motor drivers, motors, encoders, radio, antenna, connectors, charging contacts. We placed them in three-dimensional space like a jigsaw puzzle, moved each by millimetres, repacked, iterated, and measured. Only when the internals were tight and balanced with all the constraints did we allow ourselves to think about outer form. The shell didn’t dictate; it accommodated.

This approach changed the tone of the project overnight. Design meetings were no longer about wishful shapes; they were about solving conflicts between centre of gravity, access, stiffness and serviceability, EMI and antenna clearance. Out of that tug-of-war, a real product emerged, not a sculpture with electronics sprinkled inside. When you commit to this inside-out discipline, something else happens: the part count falls. And when part count falls, cost and complexity fall with it.

The most decisive step in reducing parts came from Art: what if the PCBs do more than carry electrons? What if they carry load? And thats when the electronics became the structure. Motors, sensors, and modules mounted to rigid PCB’s that doubled as the chassis. Brackets disappeared, and parts were screwed directly into the PCB’s. With careful attention to board thickness and mounting patterns, the PCBs stopped being delicate passengers and started acting like the frame. That move slashed our assembly steps and bolted reliability straight into the design. You can always add more material to brace a weak idea; it is far better to start from a strong idea that needs less material in the first place.

This is where people often ask how a tiny team of engineers can pull off what usually takes a much larger team. The answer isn’t heroics; it’s flow. An outside-in process splinters teams: industrial designers push for purity of form, electrical engineers fight to fit boards, mechanical engineers get stuck inventing clever brackets, and firmware gets a half baked product to try and make work. Inside-out collapses those arguments into one conversation: “What must be true for this to work?” When you remove ornamental decisions and replace them with concrete constraints, the rest becomes a surprisingly elegant chain of cause and effect. Place the battery and motors to hit the mass properties. Route the high-current paths to minimise resistance and heat. Choose connectors that can be mated at scale without turning assembly into keyhole surgery. Align screw patterns across mirrored subassemblies so you can reuse fasteners. The aesthetics emerge from function. And it looks good because honest things often do.

We never pretended that tabletop would be easy. Shrinking introduces new challenges: connectors that once felt fine become too large, tolerances that were “tight enough” start creating slop or friction. But those are engineering problems, not existential ones, and they yield to honest iteration. Every cycle lived in CAD first. Where we digitally iterated and treated packaging as the single most critical thing, we then ran down the failure modes and every detail before committing to manufacture another prototype. When in doubt, we asked the game to decide: if a choice made play better, it stayed; if it only made the engineering easier, it went. We got ruthless about what mattered.

Because we were designing a game, not a gadget, the robots had to be more than just the plastic and metal they were made from; they had to be communicative and emanate emotion. The balancing posture, the feel in a turn, the twitch before a sprint - all of it tells a story to the player and the opponent. A tabletop arena magnifies that language. There’s no hiding; you are inches away from the action. And because of this, the software wasn’t just about making it work it was about making it feel right, we spent days fine tuning every aspect, just capable enough, responsive, fast but not too fast. All of this goes into the overall magic of what makes a Robomate not just a robot, but something that is greater than the sum of its parts.

A word about cost, because that’s the reason we were able to do this. People often assume you need hundreds of thousands just to arrive at “working.” The dirty secret is that many budgets vanish into correcting decisions made in the wrong order. Every time you commit to an external form before understanding the internal demands, you sign up for rework. Every bracket and compromise multiplies. We didn’t buy our way past those traps; we avoided them. The shrinkwrap method is economical not because it is clever but because it is honest. If the electronics, mechanics, and game feel are the heart, then the shell is clothing. You can change clothes quickly and cheaply, and you should. But you don’t rebuild your skeleton for a fashion choice.

There’s also the discipline of part reuse. We leaned hard on mirrored geometry, common fasteners, and PCB’s that served multiple functions. We chose connectors that survive both the factory and the thousands of hits each Robomate will experience. We routed cables in straight, short runs because a neat wiring harness doesn’t just look good; it reduces failure, improves EMI, and accelerates assembly. We sized the battery to make it easily available and swappable to allow endless hours of fun.

The funny thing about doing more with less is that it becomes a habit. Once you experience the speed of an inside-out design loop, it’s hard to return to the theatre of design phases that exist to mollify stakeholders rather than to discover truth. You start trusting playtests early, even when they are uncomfortable, because they get you to the signal faster. You start trusting that a clean internal architecture will give your industrial designer more freedom, not less. When the guts are right, the skin can be anything. And when the skin changes, the guts don’t have to.

What emerged from all this is a little robot that feels like it belongs on a table - fast, expressive, robust, and simple to set up. You take it out, you know what to do, and within a minute you’re playing tag or capture-the-flag. That’s the win. That’s the moment we were building toward from the first day we watched a humanoid stumble and saw the dream crack under its own weight. We didn’t lower our ambition; we refocused it onto the experience that matters.

We’re still refining. The electronics have a few bugs that we need to sort out. The shells will evolve - protection and personality are both worth iteration. The control will keep getting easier as we watch new players adapt in seconds rather than minutes. But the foundation is set, and it is set the way foundations should be: from the inside out, constraint by constraint, mass by mass, until the shape reveals itself.

That’s how two people took a cinema-scale idea and pressed it down into something you can play with on a Tuesday night after dinner. Not with magic, not with an open chequebook, but with a method that in motorsport is second nature and in consumer robotics is still surprisingly rare. Robomates aren’t a proof-of-concept or a glossy prototype for a trade stand; they’re the beginnings of a platform for physical, strategic play you can feel. Curious to see what’s next? Join our early-bird Kickstarter list at rbmates.com.